In a former life I was, for three years, Chief Geologist at the Super Pit, Australia’s largest gold mine consuming what’s left from undergound mining of Kalgoorlie’s Golden Mile. The richest concentration of gold in the world. Mining has been carried on continuously here since 1893, when gold was first discovered by one Paddy Hannan, from the village of Quin in County Clare.

The Golden Mile in 1905. Photo JJ Dwyer. WA Museum

The Golden Mile in 2017. The Super Pit. Eastern Goldfields Historical Society

Don’t get me wrong, Paddy was not a scoundrel; I’ll talk about those characters in a bit. Paddy Hannan led a party of three Irishmen that changed the history of Western Australia, starting a rush that populated the desert and rescued a depressed economy. There are many reminders of the man – Hannan Street, Hannan’s Hotel, Hannan’s Lager (now sadly defunct) and a statue in the main street erected in the 1920s. Before the name was changed to Kalgoorlie the place was even called Hannan’s.

Paddy Hannan, taken in the mid 1920s. Photo Battye Library WA.

Hannan Street, Kalgoorlie, Postcard from 1907. Coll. Bob Singer

Crowds gather in Hannan Street, said to have been made wide enough to turn a bullock dray. Coll. Bob Singer

It’s a great story. Briefly, Paddy emigrated to Australia in 1863, escaping post famine Ireland. Eventually his six brothers and sisters followed him. Not an uncommon thing. He started in the mines of Ballarat, but prospecting was in his blood and after limited success in New South Wales, South Australia and the Southern Cross field in WA, he ended up in Coolgardie, the site of the first major gold rush in WA, in 1893. He was too late there and in June 1893 headed further east into unknown country.

John McMahon takes up the story in ‘Ramblers from Clare and Other Sketches’ (1936).

“At what is now Kalgoorlie, one of their horses strayed. During the search for the horse they found gold in some quantity. On the nearby ridge of Mount Charlotte they found water, an essential prerequisite for their work. Then Paddy found a series of gullies where gold was clearly visible. Within two days they had unearthed 100 ozs. of gold. [that’s nearly $200,000 worth in today’s value] Paddy Hannan rode to Kalgoorlie to register his claim and was awarded the space of ground which became known as “The Hannan Award” [Hannan’s Reward]. News of the find spread like wildfire, within two days they were joined by 400 men and in a week this had grown to 1,000.”

Prospecting in those days was not for the faint hearted. Searing temperatures, dust, flies, desert and lack of water and supplies meant many privations. The well resourced had camels. Most, like Paddy didn’t, but rewards such as these he, Flanagan and O’Shea found were the reason men (and women) travelled to the remote unknown on the other side of the world. Paddy was one of the lucky ones.

Prospecting near Coolgardie, WA. Photographer unknown c1894. Coll Bob Singer

Prospectors using the technique of ‘dry blowing’ to search for traces of gold. Photographer unknown. c1894. Coll. Bob Singer.

While Patrick Hannan, Thomas Flanagan and Dan Shea started the rush to Kalgoorlie, they did not discover the real wealth of the Goldfield. This lay a mile or two to the south and the real hero of the Golden Mile was Sam Pearce, another emigrant prospector from England. Just a few weeks after the Hannan’s rush he found the Ivanhoe reef, then the phenomenally rich Great Boulder mine and over the next four months, with others in his syndicate, he pegged Lake View, Royal Mint, Bank of England, Iron Duke, Iron Monarch, Associated, Consols and the fabulous Golden Horseshoe and many more.

Thus began a boom which led to the blooming of the twin cities of Kalgoorlie and Boulder, the railway arriving in 1896 and a monumental water pipeline constructed in 1903 by another famous Irishman, Charles Yelverton O’Connor (from Co Meath). His achievement of building a 350 mile pipeline from Perth to the desert was one of the great engineering feats of the day and sadly under intense public criticism of the scheme he took his life before the water arrived.

There was no denying the incredible wealth of the place but from the very beginning it attracted all kinds of financial speculation. Inevitably this led to many sharp practices and resulted in a number of financial and corporate scandals which severely damaged the reputation of Western Australia and the Golden Mile in particular. That’s what I want to talk about here.

It took only two years from Paddy Hannan’s discovery of gold at Kalgoorlie in 1893 for the first speculative bubble to take hold. The full potential of the finds was slow initially to become apparent. There was free gold, yes, but most of the gold was locked up in pyrite or in rare minerals called ‘tellurides’, containing the element Tellurium, which formed alloys with gold, making it hard to extract. Further the gold went deep very quickly. So the gold could only be extracted by deep underground mining and complicated metallurgical processes.

This need for capital created a massive market for opportunistic floats. The preferred place to raise money was on the London Stock exchange. In 1895-6, alomost 700 West Australian gold mining companies were floated. Some had real ore bodies but most amounted to little more than what we would now call “address pegging”. So long as the company had, somewhere in the name, a reference to one of the big producing mines or something associated with Kalgoorlie (or both) it was guaranteed success for the promoters. The most popular name to include was of course Hannan’s. A quick look at the lease maps prior to 1903 reveals dozens of companies using Paddy’s name linked with some of its producing neighbours to lend some credibility. Names like Hannan’s Proprietary Dev Co, Hannan’s Paringa GM Ltd, Hannan’s Brown Hill GM Co, Hannan’s Brown Hill South GM Co’, Hannan’s Star GM Ltd, Hannan’s Reward & Mt Charlotte Ltd, Hannan’s Find Gold Reefs Ltd, Hannan’s Kalgoorlie Ltd. You get the picture. None of them had anything to do with Paddy who was long gone.

Share Certificate Hannan’s Paringa GM Ltd. 1897 Coll. Bob Singer

There were also many “cashbox floats” where large sums of money were raised with no operating mines. For example the grandly titled Western Australian Gold District Trading Corporation raised £500,000, an extraordinary amount of money. In today’s terms it would be the equivalent of around $300 million.

Share Certificate West Australian Gold District Trading Corporation 1896. Coll. Bob Singer

Despite having no discernable business and no operating mine the company declared a dividend of 100%. This attempt by the directors to ensure a high price for the sale of their own shares landed Managing Director Mr L H Goodman with an 18 months prison sentence with hard labour for “conspiracy to defraud, obtaining money by false pretences, publishing false statement and misappropriation.”

A Lease map of the Kalgoorlie Gold Mines (c1897). Kalgoorlie town is at D4. Hannan’s discovery is marked as Hannan’s Lode at D3. The richest mines of the Golden Mile stretch from B6 to B9

The common feature of all these floats, even the legitimate ones, was that of the money raised, most went to the promoters and vendors with very little going as working capital (a familiar story also in later gold booms).

The London market during the ‘Westralia’ Craze was ripe for plucking by over zealous prospectors, wily WA based promoters, less-than-honest Mine Managers and so-called “experts” all feeding off one another and playing into the hands of unscrupulous London- based promoters and fuelling a frenzy among a rising middle class that we would find hard to imagine today. The only thing remotely similar but on a much smaller scale was the Poseidon nickel boom in WA in the early 70s

This activity prompted prominent author and financial journalist, JH Curle, to comment in his book ‘Gold Mines of the World’, in 1902 that

“West Australia, since the beginning of the mining there, has been a synonym for all that is bad in gold mining” and

“of the boards of directors in London I do not trust one in twenty”.

The climate was ripe for exploitation and none strode the stage larger than Whitaker Wright and Horatio Bottomley.

Whitaker Wright was born in England in 1845 and gained some formal training in chemistry and assaying in his youth. He was active in mine promotion in the US from 1875 and made and lost a fortune before returning penniless to England in 1889. Undaunted, he set to work building up his companies again and by 1897 was a millionaire for a second time!

Whitaker Wright. Contemporary newspaper sketch c1904.

His return to England coincided with the ‘Westralia’ boom and he was an active participant with his companies – the West Australian Exploring and Finance Corporation and the London and Globe Company, holding extensive share investments in WA companies.

In March 1897, Wright merged the two companies into the London and Globe Finance Corporation which had an issued capital of £1.6 million and an elite Board of notables ensuring respectability.

Londond & Globe Finance Corporation Ltd. 1898. Note signature of Whitaker Wright. Coll. Bob Singer

The company had considerable real assets including Lake View Consols and Ivanhoe mines on the Golden Mile. These he used to boost the value of many of the more speculative ventures in the portfolio.

Wright used his knowledge of his mines’ operations to indulge in what we would now call “insider trading”. He also however engaged in much more sinister activities of market manoeuvring by manipulating output from the mines, especially the Lake View Consols.

Lake View Consols GM. The jewel in the Whitaker Wright empire. Coll. Bob Singer

With the profits from his ventures, Wright became extremely wealthy. He acquired over 9,000 acres in Surrey and built a sumptuous mansion (Witely Park), complete with thirty two bedrooms, eleven bathrooms, landscaped gardens, a private theatre and an observatory.

Witley Park mansion. Home of Whitaker Wright’ Including an observatory. Photographer unknown

Witley Park Mansion. Photographer unknown

But most notable of his endeavours was a huge domed glass and steel room under a lake which he constructed. This is probably one of the world’s greatest follies. Termed a ‘ballroom’ it was actually used to house a billiard table. It was said he loved to play in the flickering light that filtered down through the murky water and the yellow glazed ceiling.

Recent photo showing the top of the ‘ballroom’ in the middle of the lake. Photographer unknown

Ballroom was accessed through this tear shaped tunnel

Spectacular domed glazed roof

Off the billiard room is a smoking room-cum-aquarium, where you could puff on a cigar while watching the giant carp. Atop this is a giant statue of Neptune, poking above the surface, and appearing as it walking on water. This folly required 600 workmen to dig out four artificial lakes and remove hills that spoiled the view.

Neptune statue atop the domed roof. Photographer unknown

For Wright, It all came spectacularly undone in 1899 when the Lake View Consols mine hit a rich patch of ore known as the “Duck Pond”. Wright at first withheld a report on the find while he sought to manipulate the market. Then, once it became public, the share price soared to £10 then £20 and ultimately to £28. Maintaining the share price at these levels depended on maintaining production which could not be done once the shoot pinched out. Whether it was Wright or the Lake View Manager who withheld the vital information that the shoot had come to an end is unclear but the resulting collapse found London and Globe, and many of its shareholders, insolvent as Wright desperately bought shares as they plunged to try and prop up the market.

The clamour for his prosecution grew, especially when official inquiry revealed that the deficiency in his companies totalled about £7.5 million. On hearing this he hid himself in the icehouse at Witley Park for a week, and then fled to New York via Paris travelling under a false name. Unluckily for him, the technology of the day meant that the warrant for his arrest was ready and waiting when he landed!

Wright was arrested and extradited to London where he faced trial and was found guilty. On 25 January 1904, he was sentenced to seven years imprisonment but before he could be imprisoned he swallowed a cyanide tablet which he had smuggled into the court and was dead within minutes.

The court proceedings revealed a trail of deceit, misinformation and fraudulent accounting all within the framework of company promotions and operations on the stock exchange. His activities were allowed to prosper because of the complicity and complacency of his shareholders who were happy to receive the benefits of very abnormal profits, without question, relying implicitly on Wright and his directors.

And then there was the wonderfully named, Horatio Bottomley.

Horatio Bottomley was born in London in 1860. He grew up in an orphanage and had no formal training, starting work as an office boy in a legal firm. His first excursion into company promotion was in 1885 in printing and publishing and he was embroiled in immediate scandal with £85,000 disappearing from the company. Remarkably he was able to avoid charges. In 1888 he founded the Financial Times primarily as a vehicle for promoting his own ventures.

Horatio Bottomley

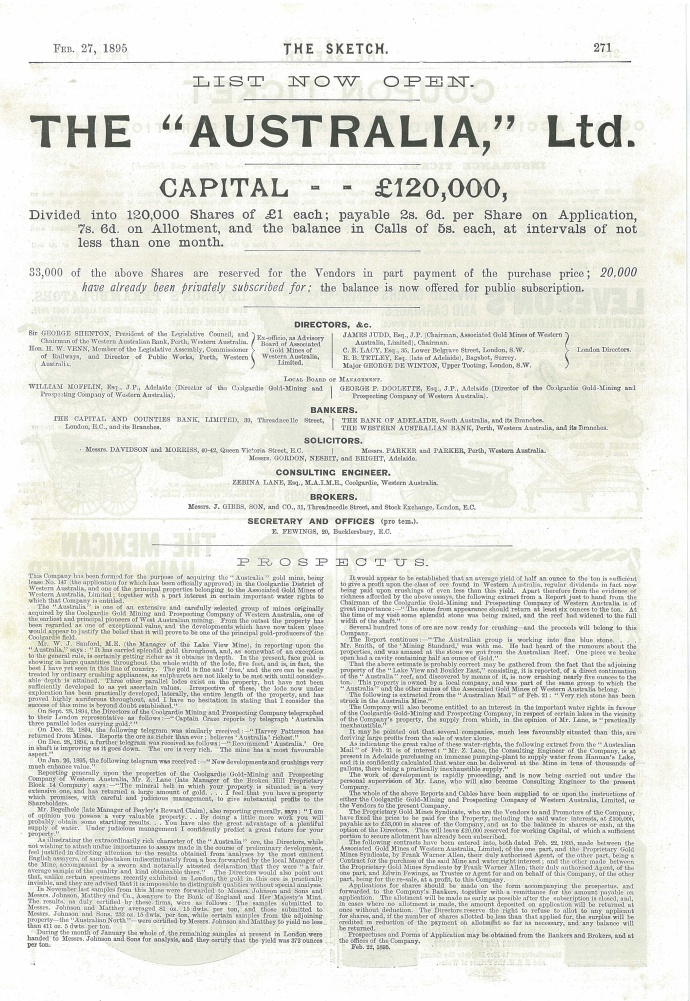

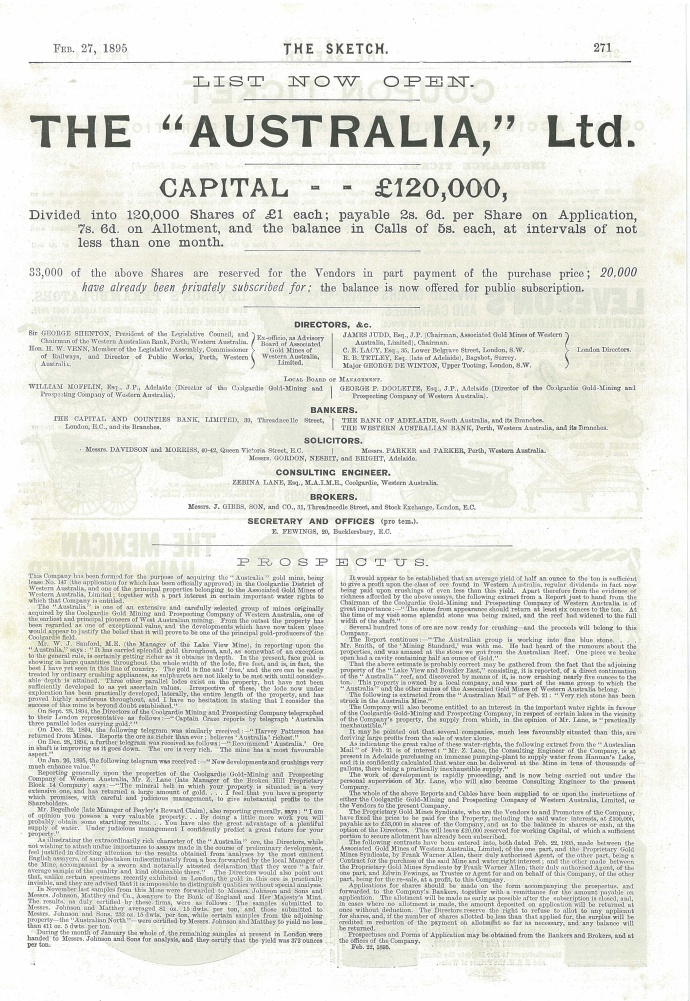

Fresh from this triumph, Bottomley got in early in the ‘Westralian’ gold boom on the London Stock Exchange. His companies West Australian Joint Stock Trust and Finance Corporation and the Western Australian Loan and General Finance Corporation were reconstructed four times each time making Bottomley a fortune. As the boom accelerated late in 1894 he was in the forefront, promoting around twenty companies in the space of just five years. Many companies were floated with worthless leases on the edge of the Golden Mile, often obtaining these leases from the Associated Gold Mines Ltd (which ran the very successful “Australia” Gold Mine) a company of which by a remarkable coincidence, Bottomley was Managing Director.

Prospectus for the Australia Gold Mine of which Bottomley was to become Managing Director. Coll. Bob Singer

His tactic was to promote to build vendor profits, by pushing the stock price for a short time, issuing a 20 per cent dividend and then letting it decline to liquidation or reconstruction. Thus, almost without exception, Bottomley’s companies were liquidated within a short time with most of the capital going to the promoters

Besides using the vehicle of promotions, Bottomley invested extensively in Associated Gold Mines of Western Australia and in the Great Boulder, companies that gave him a very handsome return as well as lending the appearance of substance to his activities. Many of his companies included the word “Associated” in their name.

One of Horatio Bottomley’s financing vehicles. Note signature of Bottomley. Coll. Bob Singer.

Bottomley’s brief but profitable career in the Australian mining sector of the London market was soon to end. The initial boom had waned and the gold mining industry on the Eastern Goldfields of WA was seeking to develop mining on a large scale. In July 1897 Bottomley changed tack and floated the West Australian Market Trust which he claimed would have “large and, perhaps, controlling interests in many of the best things in the West Australian market”. However, by the next year it was in serious difficulty with Bottomley losing heavily as the share price collapsed. Without the equivalent of Wright’s Lake View Consols or Ivanhoe mines in the Trust’s stable, public confidence in it evaporated and by the end of the year Bottomley was forced to reconstruct the company.

Like Wright, he also manipulated production at the Associated mine and stock in the company in order to promote his other company interests and to add to his personal fortunes. Late in the 1890s production at the Associated yielded spectacular results when the mine manager was instructed to stockpile rich ore for strategic processing. In mid-1900 when the deception was clear, it was reported that reserves of payable ore had been overestimated by 75%. As well, Bottomley had successively issued new capital in the company, using part to finance dividends. When production declined and the extent of overcapitalisation became apparent, the inevitable market bears (including his nemesis, our old friend Whitaker Wright) ended Bottomley’s “mining” of this section of the “stock market stope”.

Share certificate for Associated Southern Gold Mines Ltd, a Bottomley company. Coll. Bob Singer

From 1893 to 1903 it is estimated that Bottomley launched about fifty mining and finance companies with a nominal capital of between £20 and £25 million. His personal wealth at the time was estimated at about £3 million.

Bottomley maintained a superficial respectability as a businessman but remained a superlative con man. He escaped prosecution for his deeds during this period and later went on to indulge in further nefarious activities which resulted in bankruptcy three times (1912, 1921 and 1928), losing his seat in Parliament (twice) and serving seven years in prison for fraud, eventually becoming an alcoholic and losing everything before dying intestate in 1933.

Bottomley and Wright and a host of other speculative promoters, had negative consequences that hampered the early development of gold mining on the Golden Mile for many years, making it extremely difficult to raise capital for the legitimate operations. It also set in place a tradition and reputation which continued to be enhanced by the activities of Claude deBernales in the 1930s and Alan Bond and “WA Inc” in the 1980s.

But that’s another story.