The Hag of Beara

The Hag of Beara stares out to sea.

Hag’s Head in Co Clare

The Wailing Woman on Skellig Michael

Hag of Beara

Offerings left on the rock

The Children of Lir

Burial site of the Children of Lir

The Hag of Beara stares out to sea.

Hag’s Head in Co Clare

The Wailing Woman on Skellig Michael

Hag of Beara

Offerings left on the rock

Burial site of the Children of Lir

I can’t believe that in the five years I’ve lived here I hadn’t come across this place before. It wasn’t until I was chatting to my friend Oliver O’Connell, a man who knows the Burren as well as anyone, that it came up in conversation. When he saw the blank look on my face, he said “let’s forget about our plans. I’ll show it to you”.

It is hard not to be impressed when you first see it. A stunning location in a green valley surrounded by the treeless rocky hills it has towered over the landscape for centuries. A huge symbol of Church and Chieftain power. Surrounded by natural beauty and itself the stuff of legends.

Corcomroe Abbey in its fertile valley

Another view of Corcomroe Abbey bathed in sunshine.

Corcomroe Abbey viewed from the east. Note the repaired roof over the nave

It was founded for the Cistercian monks around 1195 and the church we see today was constructed in the early 13th century. The name is said to have derived from Corcamruadh, cor meaning district; cam, quarrel and ruadh, red. The church was also dedicated, more poetically, to St Mary of the Fertile Rock. It is believed that the building was commissioned by King Conor na Siudane Ua Briain (Conor O’Brien) King of the ancient territory of Thomond and a huge benefactor to the Church.

The continual relationship and support of the ruling families meant for a turbulent history for the monastery and led ultimately to its downfall. Many battles were fought in and around the Abbey and its ownership regularly changed hands. In 1268 Conor O’Brien was killed by Conor Carrach O’Loughlain, though the O’Brien’s maintained control. The monks retrieved his body and interred him in the Abbey. In 1317 yet another battle was fought this time between factions of the O’Briens and the Abbey was used as a barracks. By the end of the 14th century, the O’Cahans (O’Kane or Keane) from Derry took control of the Abbey’s lands. Sometime in the 15th century (though it is unknown how) the Tierney family took control.

With the dissolution of Catholic monasteries due to the English Reformation the Abbey and land was granted to the Baron of Inchiquin and Earl of Thomond, Murrough O’Brien, in 1554 and then in 1702 to Donat O’Brien of Dromoland, whose family retained the abbey until the 1870s when it passed into public hands.

Meanwhile the monks continued to tend the fields and maintain the abbey as circumstances allowed, but the political climate led to continued decline until the last abbott was appointed in 1628.

It is built to a standard Cistercian plan, though with some notable variations and the extreme decoration is unusual. The stonework is of such high quality it is said to have led to the ultimate demise of the five stonemasons involved, who were executed by O’Brien to prevent them repeating their masterpiece somewhere else. Hopefully they got their reward in the next life.

Over the nave there is a roof (repaired very sensitively) with exquisitely carved rib vaulting with herringbones and some floral decoration. It is lit by three lancet windows. Either side of the nave are columns with detailed carvings of human heads and flowers. Including what look like bluebells and fleur-de-lys. What is intriguing to me is the lack of symmetry of these decorated columns. This lack of symmetry is seen elsewhere, for instance in the arch over a niche on the north transept. Was this intended or was it a result of different masons working on different areas or maybe a thumbing of noses to architectural orthodoxy? At the base of the columns are further carvings of flowers (?). One intrigued me. It is unidentifiable, though to me it looks remarkably like a map of Australia which wouldn’t be ‘discovered’ for another 550 years! Such prescience.

There are many other notable features in the nave. A niche tomb on the north wall houses a life size effigy of Conor O’Brien. Beautifully carved it is one of the few examples of a depiction of an Irish chieftain surviving. He is in a serene repose, wearing a robe with pleats and a crown with fleur-de-lys decoration. He once held a sceptre apparently in his left hand (now gone) and his right holds a reliquary suspended round his neck. Love the little touch of his feet resting on a cushion. Love also that we are able to see it in situ, with no guard rails rather than have it relocated to a museum somewhere. Above this is a detailed carving of a bishop. There is an intricate sedilia (where the priests sit during the service) on this same wall.

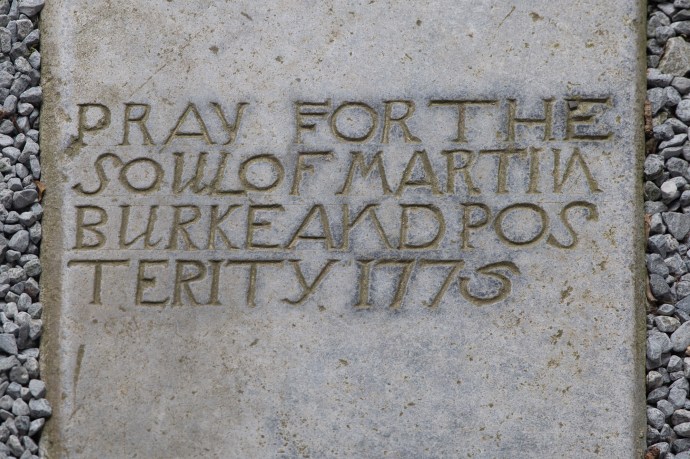

Where the north and south transepts intersect the presbytery, there are several crossing arches in remarkable condition and set into the floor throughout are grave slabs. I am a lover of gravestones and here are some of the finest I have seen in Ireland, especially those close to the altar (where the rich were allocated space). And some of the oldest, with one I saw dating back to the late 1600s. This I think reflects the patronage by the elite who could afford intricate engraving that has survived.

Corcomroe Abbey. Archway over niche in north transept. Note again assymetrical carvings with bluebells on left and fleur-de-lye on right.

Corcomroe Abbey Carved head on right hand column in southern transept

Corcomroe Abbey. Carved head and flowers on left hand columns in the south transept

Corcomroe Abbey. Effigy of Conor O’Brien.

Corcomroe Abbey. Grave slab. Elegant simplicity. Pray for the soul of Martin Burke and Posterity 1775

Corcomroe Abbey. Oliver O’Connell examines a grave slab

Enter a cap

n

Corcomroe Abbey. Grave slab for John O’Dally and Marey Flanagane. Dated 1682. The oldest I saw.

Corcomroe Abbey. Double arch over sedilia on north wall of nave. Different decorative carvings on each column

Enter a caption

Corcomroe Abbey. Beautiful detailed carving of a bishop

Corcomroe Abbey. Tomb niche of Conor O’Brien underneath carving of a bishop.

Corcomroe Abbey. Unidentified carving. Map of Australia?

Corcomroe Abbey. Floral carving at base of columns.

Corcomroe Abbey. View of the columns supporting the arch over the nave. Note the assymetrical arrangemetn of carvings at the tops of the columns.

Corcomroe Abbey. Looking towards the nave showing the arches over the north and south transepts

A walk around Corcomroe is almost spiritual. You do feel some sort of presence. And it is not surprising that stories of this abbey are woven into Irish Culture in many ways other than the clinical history of battles and chieftains or its marvellous architecture.

Indeed it is said to be haunted by the ghosts of a poet named Cearbhall O’ Dalaigh and Eibhlin Kavanagh who eloped in the 15th century and wished to be secretly married at midnight on Christmas Eve. If you know the song Eileen Aroon, which is about this episode, then you know that it didn’t end well as Eibhlin’s father caught up with them that night.

You will also feel perhaps, when you walk around, the inspiration that Yeats must have had when he chose to use it as the backdrop for his play on Irish freedom, The Dreaming of Bones.

That feeling stayed with me long after. Thanks, Oliver, for introducing me to this special place. Highly recommend.

I have stumbled onto historical mining in a number of places in Ireland in my travels. Particularly at Allihies and Mizen in West Cork and along the so-called Copper Coast in Waterford. However, I had no idea of the significance of copper mining in Killarney, and only came across it by chance recently when exploring Killarney National Park’s other delights.

19th Century mining of copper underpinned many fortunes for its British landowners. In Castletownbere in West Cork, it was the Puxley’s and Killarney it was the Earls of Kenmare and then the Herberts, who funded their magnificent home at Muckross from their mining wealth. Ironically the mansion at Muckross was completed in 1843 as the Famine ravaged Ireland. But the saga of mining in Killarney goes back much further, deep into Neolithic times.

Muckross House built by the Herbert family with money from their mining fortune

Muckross House. Built 1843

When we talk of mining history in Australia, we think back to the first gold rushes in NSW and Victoria, which were in 1851, or Australia’s own copper boom, which started in South Australia in the 1840s. Mining effectively ended Australia’s time as a penal colony and led to an explosion of free immigration. So it took a bit to wrap my mind around the mining heritage of a country that goes back thousands of years.

Mining has taken place at two locations on the Killarney Lakes, Ross Island and on the Muckross Peninsula. Mining there reflects human occupancy from the end of the Neolithic Period and the early Bronze Age (2500-1800 BCE) through Christian times (8th Century) to industrialization in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Ross Island is the earliest known site for copper mining in Ireland. The activity has been dated by the discovery of Beaker pottery by a team from National University of Ireland Galway in 1992. The so-called Bell Beaker culture is named after the inverted bell-shaped pottery vessels found scattered throughout Western Europe and dated in Ireland from 2500 BCE to 2200 BCE. This has been confirmed by radiocarbon dating at the site.

Beaker vessel characterstic of the style of the Bell Beaker culture, fragments of which were used to date the Ross Island mining site. Photo credit: http://curiousireland.ie/the-beaker-people-2500-bc-1700-bc/

The true Bronze Age in Ireland (that is when copper was alloyed with tin or arsenic to manufacture weaponry and tools) started around 2000 BCE. Prior to this was the ‘Copper Age’ and copper from Ross Island would have been used for daggers or axe heads or other copper objects and was traded widely. Chemical fingerprinting and lead isotope analysis shows that Ross Island was the only source of copper until 2200 BCE in Ireland. Not only this, but two-thirds of artefacts from Britain before this time show the same signature. And Ross Island copper is found to be present in artefacts found in Netherlands and Brittany. After this time other mines from southern Ireland became more important.

So, Ross Island saw the transition from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age. Frankly, to me as a mining geologist, to be able to stand on the place where the mining took place that underpinned this highly significant transition in human development in Ireland was, for me, a special experience.

The early miners exploited a rich band of oxidized copper ore within the limestone through shallow cave-like excavations, tunnels and chambers, most of which were damaged by subsequent mining. Some of the surface ‘caves’ are visible today behind a rusting iron fence though the view is unfortunately heavily obscured by vegetation, which has been allowed to grow unchecked.

Bronze Age mining excavation Ross Island

Bronze Age mining Ross Island

Probable Bronze Age mining excavation with later 18th Century stone walls.

These openings were made in the days well before explosives, by lighting fires against the rock face to open fractures and then pounding the walls with stone hammers. The broken rock was then hand sorted and the separated ore was converted to metal by smelting in pit furnaces.

The last of the first phase of mining from this site is dated at 1700 BCE. Mining lay dormant for centuries then, but in the early Christian period was a Golden Age of metalworking in Ireland, when such treasures as the Tara Brooch were produced. Killarney was one of the centers of metallurgical and artisanal skills. Excavations at Ross Island have found small pit furnaces that date from 700 AD suggesting that ores from here were used to produce metals for the production of such objects.

Another thousand years passed before the final chapter in the exploitation of the wealth of Killarney copper played out.

This last phase of mining commenced in the early 18th century. The first attempts at extracting lead in 1707 and then again to work the mine in 1726 failed. In 1754 Thomas Herbert commenced mining under an arrangement with the then landowner, the Earl of Kenmare. Mining was difficult due to flooding from proximity to the lake edge and for the next fifty years was sporadic.

I must digress for a moment. In 1793 Thomas Herbert invited a mining consultant Rudolf Raspe to advise on the mines. Why do I mention this? Raspe was German and author of The Fabulous Adventures of the Baron von Munchausen (published in 1785). You might have seen the movie or heard of ‘Munchausen Syndrome’ but I grew up with these fantastical stories read to me by my father. Who would have dreamt of a connection between these far-fetched tales and copper mining in the west of Ireland. Anyway the poor fellow didn’t have such a Fabulous ending dying of scarlet fever a few months later and being buried in an unmarked grave near Muckross.

Meanwhile mining on Muckross Peninsula started in 1749 on the Western Mine and by 1754 the company had raised some £30,000 worth of copper ore, which was shipped to Bristol for smelting. This closed in 1757 and operations commenced on the Eastern Mine opening for short periods in 1785 and again in 1801. Operations resumed on the Western Mine in 1795 but these failed due apparently to mismanagement. Little more was heard of this mine and it was considerably less successful than its neighbour.

Mining spoil at Muckross Mine seen from the lake

Muckross Peninsula. 18th Century smelter building

Inside smelter building showing unusual curve flue. There were at least three smelting furnaces in the structure.

Muckross Peninsula. Old mine building

But things might have been very different. A dark crystalline mineral was encountered which oxidised to a very bright pink. It had no copper and so was discarded. One miner recognised it as the cobalt ore, cobaltite (CoAsS), with its oxidized form, pink erythrite (Co3(AsO4)28H2O). This man quietly removed twenty tons of this ‘rubbish’ undiscovered. When the proprietor later realised its value, it was too late. It had been removed by his helpful employee, or mined as waste and thrown away to expose the copper ore. Reminds me of the non-recognition of the gold rich Telluride ores in Kalgoorlie in 1893, which for years were used to surface roads, until a way was discovered to extract the gold. Needless to say, the roads were ripped up.

Erythrite from Muckross. Photo credit: Online Mineral Museum

Back to the Ross Mine, which at the beginning of the 19th century had another renaissance. The Ross Island Company obtained a 31 year mining lease from Lord Kenmare in 1804, Work commenced on the Blue Hole on a rich lode of lead and copper. Mining continued until 1810 by which time it had become unprofitable.

Blue Hole Mine open pit

Northern pit Blue Hole Mine. Mining completed 1810

The operation was restarted by the Hibernian Mining Company (1825-9). Both struggled with the perpetual problem of flooding. One solution suggested was to drain Lough Leane; this did not go down too well as you can imagine, particularly with the local boatmen. In the end a large coffer dam was built on the shore and water pumped into it from the mine. Part of the dam is still there. Bigger and bigger pumps were required and ultimately by 1828 they were unable to deal with the water and the mine closed. Most of the Western Mine area is now flooded as the dam walls have been breached

Eastern coffer dam.

Part of Western Mines area flooded by breached dam wall on left.

Ross Island. A walled off limestone cave with steel door. My hunch it was used as a magazine.

Old shaft near Blue Hole mine

Site of Old Engine House Ross Island Mine

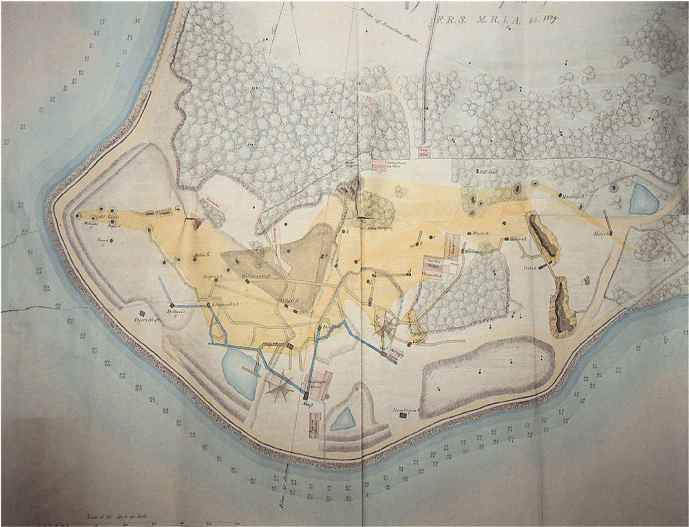

Wandering over the site today does not give a true sense of the scale of mining in the early 19th century. This map by Thomas Weaver from 1829 shows the fifty or so shafts, underground tunnels and surface buildings from this phase of operations.

Thomas Weaver map of Ross Island mine workings 1829. Photo credit NUIG.

But mining grew out of favour and conflicted with the rise of tourism to the area. No more mine leases were granted after 1829 by the Herberts, who by this time had transitioned from mining entrepreneurs to landowners. The area was carefully landscaped, with the infilling of shafts, flooding of the Blue Hole, the demolition of buildings and the planting of trees. Subsequent forest growth has softened the historic footprint of the mining

Mineral exploration is now prohibited in the National Park so the remarkable 4,500 year history of mining here has come to an end. Public awareness however of this important site is increasing with the creation of a Mining Trail and explanatory signage at the site. To me, places like this are as important as Glendalough and Ceidi Fields and their preservation is so important.

I am ashamed to say that after five years in Ireland I only discovered this place by accident. But find it I did, and I will be back there as soon as I can be.

Much of the material for this blog came from the informative website of the National University of Ireland Galway who completed the archaeological study of the historical mining sites in 1992. http://www.nuigalway.ie/ross_island/. My thanks and acknowledgement to them.

Some institutions in Ireland die hard. One is the Puck Fair. Held annually in Killorglin in Co Kerry in August, it is surely one of the country’s longest running public events. As with many of these things though, the written record is scant and it is not clear exactly how old it is. There is a reference in 1613 to a local landlord, Jenkins Conway, collecting a tax from every animal sold at the ‘August Fair’ and even earlier there is a record from 1603 of King James I granting a charter to the existing fair in Killorglin. So let’s just say it is well over 400 years old.

The main street of Killorglin is choked for the Puck Fair

Puck derives from the Irish Phoic, meaning He-goat. Again, when the fair became associated with the goat is also shrouded in mystery. The story I like tells how in 1808 the British Parliament made it unlawful in Ireland to levy tolls on cattle, horse or sheep fairs. The landlord of the time lost his income and on the advice of then budding lawyer Daniel O’Connell (yes, that Daniel O’Connor), proclaimed it a ‘goat fair’ and charged his tolls as usual believing it was not covered. To prove it was indeed a goat fair a Phoic was hoisted on a stage and proclaimed King Puck.

Whatever the truth, a male wild goat is still today crowned King and hoisted in a cage up a tower where he remains for three days before being released back into the wild. The crowning of the goat though, I have to say, was a disappointment. Conducted on a stage under the tower, with its steel barrier that restricted vision, the goat was held by two burly yellow-coats and surrounded by photographers. A young schoolgirl, the ‘Queen of the Fair’, placed the crown on its head. Well, I think that’s what happened. It was really just set up for the publicity shots, as the audience could see nothing. Placed in the cage the goat was then hoisted up for all to see, its crown a little shakily slipping below its horns.

Behind that phalanx there is a goat getting crowned

The King of the Fair is hoisted up the tower

King Puck

The fair brings out the crowds for a great day out. There is a horse fair in a nearby field, with all the usual horse-trading that happens. I happily spent an hour wandering here clicking away. There was plenty to keep me enthused and bemused.

The horse fair is held in a field adjacent to a ruined church and graveyard

Now that’s style

Like father like son

You have been warned.

The cheapest pee in town. Just a half a cent!

There are rides, a parade and plenty of characters to fill the pubs and the streets. Every vantage point was taken. The bright sunshine, when I visited in 2015, provided an opportunity for the colleens to strut the summer fashions. I love the way traditional music is never far away from an Irish event, with entertainment on stage and in teh nearby pubs, dancing in the street or a brush dance in a pub.

The long and the short of it.

A great vantage point

Even manequins are keen to strut their stuff

Dancing in the streets

Well known piper, Brendan McCreanor, from Co Louth entertains the crowd

Swept away by a brush dance

A chance to dress up

A chance to dress up II

Defying gravity

The Puck Fair is always held on 10, 11 and 12th August so mark it in your calendar.

This story has everything. It takes place over 3,000 years and is full of intrigue and mystery, the struggle for survival, buried treasure and fairies and avarice.

It started for me with a visit to the National Museum in Dublin in 2014. I was in a rush and had little time to study the exhibits, but a particular interest was the collection of bronze age gold artefacts, so I took lots of photos to review later. And then promptly forgot about them. I rediscovered those photos the other day and was struck by something that I hadn’t noticed at the time. Some of the exhibits came from County Clare. In particular from the, so named, Mooghaun Hoard or the Great Clare Find, near Newmarket-on-Fergus. This hoard dated at 800-700BC was the largest hoard of gold jewellery ever found in Europe. It is thought to have originally comprised up to 300 pieces and the story surrounding it is fascinating.

Part of the gold hoard from Mooghaun comprising five collars, seven bracelets two neck rings and a ring. Replicas of 120 bracelets and two ingots which were also part of the hoard but are now lost. National Museum Dublin.

Three gold collars. Mooghaun Find. National Museum Dublin

The gold was discovered by a number of railway workers clearing land for the Limerick to Ennis railway, on a right of way near Dromoland Estate, in 1854. They unearthed a stone box containing twisted metal which, at first, they did not recognize and indeed threw some into the nearby lake. They soon realized it was however dirt encrusted gold. With mad haste they ran 1.5 miles to the town of Newmarket, where some of the gold was quickly melted down by silversmiths keen to profit.

The rush to melt it down may have been driven by thoughts this was ‘fairy gold’. Ancient legends speak of bones and charcoal contained in buried vessels that in reality were golden coin and ornaments belonging to the ‘good people’, or fairies, and that they returned to gold during the night. But if watched with proper precautions and ceremonies, the fairy gold at daybreak would still remain gold. Their haste may have been a desire to extract the wealth before it returned to bones and ash.

Nevertheless it is an irreparable loss to Ireland’s heritage. It is believed that 34 pieces have survived, the rest melted down for bullion value. Gilt-bronze casts were made of some of the pieces prior to their destruction. Three months after the find there was an exhibition of remaining pieces, which were for sale. Due to the expense, the Royal Irish Academy acquired only 12 pieces, which included five collars and two neck-rings and The British Museum purchased a collar and thirteen bracelets. The rest were melted down.

How they came to be deposited there is unknown. They may have been a gift to appease the gods or they may have been hidden to avoid being lost to attacking tribes. Whatever the reason it seems we will never know. Then I discovered something really interesting. The find is less than a kilometer from the ruins of a massive megalithic structure, the impressive Mooghaun Hill Fort or ‘Hill of the Three walls’, the largest hill fort in Europe. Researchers agree that the trove must be connected in some way.

Newmarket-on-Fergus is about 45 minutes drive from my home so I had to have a look and headed out there the very next day. It was easy enough to find. The monument is controlled by the OPW. A car park, well laid paths and lots of helpful signage. The winter weather was kind enough with rain holding off.

The Fort occupies an entire hill with its three massive concentric ramparts covering an area encompassing 27 acres. Within the walls would have would have been a community ruled over by a local king and his community of followers and subjects. There would have been housing for a few families, livestock and areas for crops. It is now covered in a forest of birch, ash and hazel but at the time of construction would have stood dominant, on a 300m high bare limestone hill, as a monumental statement of power and authority. The king would have controlled an area of 170 square miles with perhaps 9,000 people. It is estimated that over 2,000 of these would have been engaged in constructing the walls which may have taken up to 20 years to complete.

The walls have degraded significantly, overgrown in places and mostly linear piles of rubble. In places though signs of the original facing of the walls can be seen

Wall of the Inner Rampart, Mooghaun Hill Fort

Inner Rampart showing original (?) facing.

This community may have occupied the site for 1,500 years and while there is no record of the cause of its demise, by about 500AD the abandoned site was occupied by a new community. They made their homes there, using stones from the original hillfort’s ramparts. They built a number of circular drystone cashels of which two survive in remarkable condition, having been repaired and adapted over the years. One was used for picnics by the inhabitants of Dromoland Castle in the 18th century.

View of Upper Cashel. Mooghaun Hill Fort

Lower Cashel. Moohaun Hill Fort

Detail of wall of Upper Cashel

After viewing with wonder the fort and its rubbly remains, I rambled on through the surrounding woods. A truly beautiful and peaceful place. Depite the winter having stripped the trees of foliage it was quite a treat with tall straight birch, ash and hazel projecting skyward from a thick carpet of leaf litter.

Many of the trees, boulders and walls are covered with a lush green assemblage of mosses, ferns and ivy creating intriguing vertical gardens contrasting with the brown forest floor. In the misty, hazy light it was invitingly beautiful.

I wandered on, losing track of time, before reaching the end of the woods, defined by yet another wall, built this time by the Dromoland Estate. The Estate is surrounded by a wall, in many places with coping comprising vertical limestone slabs.

Wall separating Mooghaun Woods from fields in the Dromoland Estate.

Dromoland Estate boundary wall surrounding Mooghaun Woods

Boundary wall for Mooghaun Woods. with coping.

Coping on boundary wall here has vertical limestone slabs

I met a local, Tommy, taking a walk through the wood. We chatted for a while and I asked him if he knew where the gold hoard was found. As it turned out he lives adjacent to it and gave me directions as to where it was. I found the spot which was where the railway passes close to a small lough (this is the lake which figures in the descriptions of the find). Standing on the railway bridge it was easy to imagine the scene that day in 1854 and the life-changing excitement that the discovery brought to these navvies.

Location of the Mooghaun Hoard find. It is thought the find was roughly at the position where the train is, adjacent to the lake

With my thoughts planted firmly in past millenia and the exigencies of life in ancient times I walked on. I passed a ruined cottage. This jolted me back to this century. The ruin interested me because it was a stone cottage with a corrogutaed iron roof, which in my experience in Ireland was unusual. It gave the whole building a rusty red appearance. This had once been a comfortable residence and though overgrown now had lovely views of a large turlough beyond grassy slopes. A peek through an open window suggested its abandonment but as is the norm here I could only speculate on the back story.

Abandoned cottage Mooghaun North.

Inside the abandoned cottage at Mooghaun North

Oak tree and outbuilding at abadoned cottage

On the way back to my car, though I met Tommy again returning from his walk. I thanked him for helping me find the site and took the opportunity to ask about the cottage. He told me it had been occupied by two bachelor brothers, who died in the mid 90s. They passed it on to heir niece who was settled elsewhere so declined to move in. Since then it has lain abandoned and crumbling. Sadly it is beyond repair now. Tommy added that it was used as a polling station for elections, a common practice it would seem, with private houses being used in remote communities where many could not access a booth otherwise.

So there it is. That visit to the museum five years ago opened up a story highlighting yet again the fascinating, interwoven connections of Ireland to its people, land, culture and heritage, and the amazing discoveries that I continue to make.

Invitations like this don’t come around very often. Certainly not for me and certainly not in Ireland. Friends, Jeanne and Natasha from Albuquerque in New Mexico (in fact you can read about how we met here) were visiting again, this time for the The Irish National Hot Air Balloon Championships in County Offaly. Held annually since 1971, this is the longest running national ballooning event in the world and the biggest in Ireland. Invitation only, up to 40 balloons from around the world, fly each year in what promised to be an incredible spectacle. It was held over the week of September 24 to 28th.

Jeanne Page and Natasha Coffing. My hosts.

There was a chance I could crew. Who wouldn’t want to be part of that? But I ummed and ahed. I was still recovering from three weeks in the US. On Tuesday it was still just a thought. By Wednesday I had the kind offer of a bed from a musician friend at her magnificent BnB in Kinnitty, Ardmore Country House. House. That sealed it for me. A night or two in quite possibly one of the best BnB’s in Ireland and some fiddle tunes was the extra incentive I needed.

Ardmore Country House BnB in Kinnitty. My home for the duration.

It was only a couple of hours drive and in dull weather I arrived at the launching place, which was the dramatic gardens surrounding Birr Caste and Demesne. Preparations were well underway for the late afternoon flight. I couldn’t find my friends from Albuquerque so I watched with great interest the activities feverishly underway, as crews readied their balloons.

Balloons were being unfurled, baskets were being loaded, flames were being thrown and one by one the giant multicoloured bubbles stood upright and drifted slowly into the hazy evening. I started to put some pieces of the jigsaw together but I really had little idea of what I was watching. As the last balloon drifted over the castle I came to the realization that my friends were in the air and that they probably had to land somewhere. So I asked someone, who seemed to know, who said they were heading to Kinnitty, about 10 km to the east. Well, turned out she didn’t actually have much more of an idea than me, or perhaps the wind didn’t cooperate but, in my haste to get to Kinnitty, I failed to notice they were actually heading northeast rather than east.

I caught up later that evening with Jeanne and Natasha at Dempsey’s Bar in the charming village of Cadamstown, 10 minutes north of Kinnitty where a regular trad session was being held. The word had got out and the pub was crammed with musicians and with ballooning people. They were lucky. It was terrific music led by local box and banjo legends, the Kinsella brothers, and at least twenty other musicians with a high energy mix of tunes and songs. Jeanne and Natasha had bought their harps with them from the States and treated us to some lovely duets.

Traditional music session in Cadamstown. Natasha and Jeanne join in on their harps.

In among the tunes we discussed the possibility of a flight the next morning. My education in ballooning continued. A decision on whether flying was possible would be made at the Pilots’ Briefing at 6:30 am. Weather conditions, in particular wind speed and direction, were the primary factors. Then the teams will move to the launch site and each pilot will make the decision as to whether they will fly. I couldn’t be guaranteed a spot in the basket but if that didn’t happen I could join the chase crew. They are charged with following the balloon to be there wherever it lands, get permission from the local farmer and collect and transport the crew and the balloon back to Birr. It looked promising.

So next morning I was there. The wind was good and the weather was fine and the decision was a Go. There was a problem though. Patchy thick fog had descended and there were worries about visibility. So the crews made their way to the site for individual pilots to make their own call. It had been a cold night and frost was still covering the ground, the wetness soaking through my waterproof boots to my toes.

A few set up and started inflating their balloons but most pilots waited. The mist had created an eerie atmosphere and while the delay was disappointing it was a hugely appealing light and plenty of opportunities for the photographer in me to experiment.

Birr Castle rises from the mist

Waiting in the frost and mist for the sun to rise

Autumn reflections

The sun bursts through the fog

A magical misty morning. More like a Monet painting.

Island in the mist

As the sun rose the feeling was that the fog would burn away and a few started to take to the air. Our pilot Steve Coffing (who just happened to be Natasha’s uncle), though remained cautious. It seemed obvious but the primary requirement was that you need to see the ground. There was still doubt about whether the fog had lifted sufficiently to give this required visibility. We waited.

Most balloons were now in the sky, but then the fog came back in and a number of the last to lift off returned to the ground. Finally Steve decided when it became clear that we had run out of time and called off the morning flight. I was actually not particularly upset as I felt happy that despite my frozen fingers, I had captured some great images. I’ll leave it to you to judge.

We adjourned for breakfast at a local cafe. Steve was confident the weather would be good in the evening and renewed my invitation to fly. He suggested I be at the afternoon briefing at 4.30 pm.

Once the fog lifted it turned into a cracker of a day. Perfect to explore the nearby Sieve Bloom. These low mountains straddle Offaly and Laois and are a wonderful mix of thick forests of spruce and pine, ancient oak and beech forests, open bog land, lakes and mountain streams cascading through mossy glens. It is a hiker’s’ paradise, so that’s what I did. But my mind was elsewhere.

On tenterhooks I attended the 4.30 pm briefing. It was a Go decision for the evening flight. But things had changed a little and the balloon that I had planned to fly in was needed for a check flight to maintain the owner’s licence. Steve managed to get a piloting spot on another balloon but I was told that balloon was full. Then fate stepped in. Nikki and Dylan, an Aussie couple I had met the previous night at the session in Cadamstown, came to my rescue. Friends of the owner of the balloon Steve was flying. they had already flown a couple of times earlier in the week. To my eternal gratitude they gave up their spot and it was Up Up and Away [Oh dear, I never thought I could be so cheesy as to use that line!]

I now joined the readying of the balloon for flight. Like me, most of my readers will not have flown in a balloon before. Well I became an instant expert. The physics is simple really. The nylon or dacron ‘envelope’ is filled with air using a large fan and this is heated until the balloon is upright. A basket is suspended underneath which carries up to four passengers, the pilot and a heat source. The heat source is an open flame fueled by propane, carried in tanks on the basket. The heated air reduces the density of the air inside the envelope compared with the colder air outside causing it to rise. The skill of the pilot comes in knowing how much heat to apply to make it rise or fall. Rapid descent can be achieved by opening the vent at the top with a rope causing the hot air to escape quickly. There is limited ability to change direction and reading the wind, which can change dramatically at different heights, is part of the skill of flying.

Simple really. A great achievement though for the Montgolfier brothers who built the first manned balloon in 1783. Love the way when they were testing it for manned flight, they proposed that convicted prisoners should be used for the first pilots. Dispensable.

So I watched the preparations with keen interest. The equipment is actually quite compact and is carried in a customized trailer.

Basket being removed from trailer

First the basket is prepared. The burner is then mounted over the four corners of the basket and the legs wrapped with a protective insulation.

Burner being mounted over basket

legs wrapped in insulating material

Burner is tested.

The propane is connected to the burner and the burner tested. The balloon is then unwrapped and laid out next to the basket which is now on its side. Inflation begins with a large fan. As the balloon expands the burner is turned on sporadically to heat the air. This process takes only a few minutes and when the balloon is full and the pilot is ready the heating is increased which pulls the basket to vertical.

Balloon is unwrapped and laid out. Everyone pitches in.

Balloon is filled with air

Vent flap is secured

Fan used to fill balloon

Air is heated once filled

Heating continues until balloon stands vertically

IT is now ready for take off. Passengers board. Joining Steve and myself was John Kelly, a local publican, with a deep knowledge of the surrounding landscape. We had a briefing. There were only a few simple rules. Keep an eye out for other balloons and livestock and power lines and communicate this with the pilot. And oh, Don’t get out of the basket. My total agreement with that one. I was definitely ‘crew’ now. We were ready to go.

There was a roar from the burner shooting flames into the balloon above and we rose effortlessly. There was no real sensation of take off. The ground just seemed to move away from us. In between the bursts of noise of the burner it was deathly quiet. Just this wonderful relaxing calm.

Lift off

Most balloons were ahead of us but as we rose, I could see them spread out before us. Some stayed low. Others were thousands of feet above us. Birr Castle and its magnificent grounds disappeared from view. Steve took us up to 2,000 ft just to show us what it felt like. Sometimes balloons go to 5,000 ft particularly if they have passengers who are sky diving. Oh my god. The thought of throwing yourself off this little basket from this height totally freaked me out. Fair play to those who can happily do this and actually much prefer it to jumping from a light plane as they have no forward velocity.

Leaving Birr Castle I

Leaving Birr Castle II

Leaving Birr Castle III

Who knows where we will end up?

Balloons fill the sky

At all levels

The balloon ‘Twister’ flying low. This was the balloon I was originally to fly in.

Bliss.

Our pilot Steve holding all the ropes

Soaring above the swans

Magic evening light

The evening sun casts our balloon shadow on the glowing trees

Looking for a landing spot

We drifted effortlessly with only occasional use of the burner for minor adjustments to our flight while I just breathed in the late evening light and dealt with the challenge of capturing the feeling as best I could with the camera. It wasn’t a point and shoot exercise. I found I needed to make constant adjustments to the exposure to compensate for how much sky there was or where the sun was. I was learning quickly. We were up there for nearly an hour. One wonderful hour. I know I would do a better job next time.

We made preparations to land. Steve was in constant radio contact with the ground support team. He had to consider a lot in deciding where to land. An open field with no trees, no power lines, no livestock, not under cultivation, not a bog and easy access. Lots to consider. Once he has decided the ground crew tries to determine the owner and seeks permission Normally the pilot would wait for clearance. In this case the landowner was thrilled we were landing in her paddock.

You have to admire the skill of the descent. It was controlled and steady with Steve adjusting both the horizontal ground speed and the descent speed. He jokingly told stories of a tradition in some places of leaf grabbing as pilots scrape the tops of trees.

But not this time. We touched the ground bounced a couple of times, dragged a little and then stopped . Remaining vertical all the time. A quick exit and the retrieval crew including Nikki and Dylan, who were waiting a short distance away stepped in to manage the deflation and unhooking of the basket.

Safe landing

Dylan and the chase crew was there to meet us

Pilot Steve Coffing and my fellow passenger John Kelly pose for the family album.

Nikki at the end of her tether

There was a celebratory atmosphere with the crew participating equally in the thrill that us virgin flyers so obviously had had. Of course once the balloon was packed and loaded there was just one thing to do. A few quiet ales and some songs (I had my guitar in the car) back in John Kelly’s pub in Birr. Perfect end to the day.

I had an amazing three days. So many people to thank for making this all possible. Jeanne Page and Natasha Coffing for thinking of me, Christina Byrne for sharing her house and her music, Steve Coffing for piloting with skill and aplomb and for making us feel comfortable and relaxed, Nikki and Dylan for giving up their spot in the basket and for making me a little homesick for a Home Among the Gum Trees, the owners Graeme and Judy Scaife for sharing their balloon with so many people in and outside of the ballooning community, to my fellow passenger John Kelly for helping me understand the landscape we were flying over and to Shane Page for sharing some tips for photographing balloons. The organizers need to be complimented also for there effortless coordination of a lovely relaxed few days of ‘competition’.

I think I might do that again.

Balloons come in all shapes and colours